New Jersey’s public school system is undergoing one of the most significant demographic shifts in its modern history, as more than 130,000 students—nearly one in every eleven children enrolled statewide—now arrive at school each day still learning how to speak, read, and write in English.

During the 2023–2024 school year, roughly nine percent of New Jersey’s public school population was formally identified as Multilingual Learners, also known as English Language Learners. Behind that statewide figure is a deeper transformation unfolding inside classrooms across urban, suburban, and even rural districts, reshaping instructional models, staffing needs, curriculum design, and family engagement strategies.

Multilingual Learners are students whose primary language at home is not English and who require additional instructional support to fully participate in academic coursework. In practice, the designation reflects a wide range of lived experiences—from newly arrived refugee children entering American schools for the first time, to U.S.-born students raised in bilingual households, to students who have spent years in New Jersey classrooms but are still developing academic English fluency.

District leaders say the surge in multilingual enrollment reflects both global migration patterns and the evolving linguistic diversity of New Jersey communities.

A growing share of students entering New Jersey schools in recent years have arrived from countries affected by war, political instability, and economic disruption. Districts across the state report enrolling new students from Ukraine and Afghanistan, alongside continued arrivals from Central and South America and the Caribbean. Many students come with interrupted formal schooling, limited literacy in their first language, or trauma-related learning challenges that complicate language acquisition.

At the same time, New Jersey’s long-established immigrant communities continue to expand. Approximately 27 percent of all public school students in the state now speak a language other than English at home, making multilingualism an everyday reality inside many school buildings.

Spanish remains by far the most common home language among multilingual learners, accounting for roughly 70 percent of identified students. However, districts are also serving rapidly growing populations of Arabic, Portuguese, Haitian Creole, Chinese, and Korean speakers, as well as students who speak dozens of less common languages that may only appear in small numbers within a single school.

The complexity of this population is one of the defining challenges facing New Jersey educators.

Contrary to common assumptions, learning English is rarely a quick process. Education researchers consistently find that while students may acquire conversational English within a year or two, full academic proficiency—especially the language required for reading complex texts, writing essays, and understanding advanced math and science concepts—can take five to seven years or more.

Even after five years in U.S. schools, only a small share of New Jersey’s multilingual learners are officially classified as fully proficient in English. For many students, especially those who arrive at older ages or with limited prior schooling, progress unfolds gradually and unevenly.

State education leaders emphasize that this reality does not reflect a lack of ability. Instead, it underscores how demanding academic language development truly is, particularly when students are simultaneously expected to master grade-level content across all subjects.

Under New Jersey’s Bilingual Education Code, school districts are legally required to identify and serve students who need language support. Every student entering a public school completes a home language survey, which helps determine whether additional screening is necessary. Students who indicate exposure to a language other than English at home are then assessed using state-approved language proficiency tools.

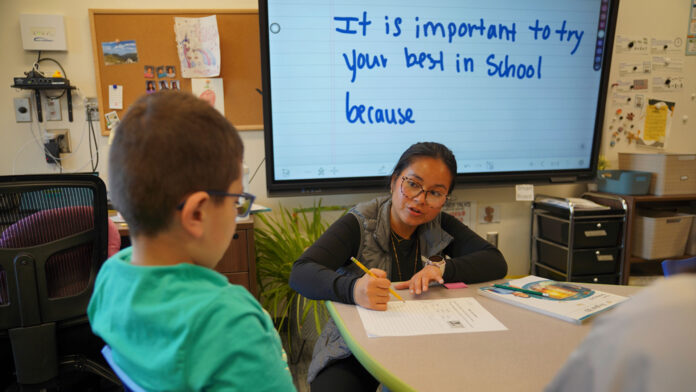

Once identified, students must be placed into appropriate language support programs. In most districts, that includes English as a Second Language instruction integrated into the school day. Larger districts and those with higher concentrations of multilingual students are also required to operate bilingual education programs that allow students to learn academic content in both English and their native language.

In recent years, a growing number of districts have also invested in dual-language immersion programs. These programs intentionally mix native English speakers and multilingual learners in classrooms where instruction is delivered in both English and a partner language—often Spanish or Mandarin—with the long-term goal of producing students who are fluent, biliterate, and academically prepared in both languages.

Advocates say dual-language models offer benefits well beyond language acquisition, including improved cultural awareness, stronger literacy skills, and long-term academic advantages for both multilingual learners and native English speakers.

Still, implementation remains uneven across the state.

District administrators consistently cite staffing shortages as one of the most serious barriers to fully meeting students’ needs. Certified bilingual teachers and ESL specialists remain in short supply, particularly in high-need districts where multilingual enrollment is growing fastest.

In some schools, a single ESL teacher may be responsible for supporting dozens of students spread across multiple grade levels and classrooms. That reality can limit the amount of individualized instruction students receive and make it difficult to align language development with grade-level academic expectations.

Recruitment challenges are compounded by rising costs of living in many parts of New Jersey, which make it difficult for districts to compete with neighboring states or private-sector opportunities. Teacher preparation programs have also struggled to produce enough bilingual-certified educators to meet statewide demand.

Beyond staffing, districts face mounting pressure to provide culturally responsive instruction that recognizes students’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds as assets rather than obstacles. Educators are increasingly trained to integrate students’ home languages into classroom discussions, encourage family participation, and adapt curriculum materials to reflect diverse communities.

Family engagement has become another critical pillar of multilingual education. Many parents of multilingual learners face language barriers themselves when navigating school systems, attending meetings, or accessing special education and academic support services. Districts are expanding translation services, multilingual parent liaisons, and community partnerships to bridge those gaps.

School leaders say effective communication with families often determines whether students receive timely academic interventions, social-emotional support, and consistent attendance.

Technology is also playing a growing role. Digital translation tools, multilingual learning platforms, and adaptive literacy programs are increasingly used to supplement classroom instruction, particularly in districts with limited staffing. While these tools cannot replace certified educators, administrators say they help close access gaps and provide students with additional practice outside traditional instructional periods.

Despite progress, equity concerns remain.

Education advocates warn that multilingual learners are more likely than their peers to experience academic delays, higher rates of chronic absenteeism, and lower access to advanced coursework if support systems are stretched too thin. In districts already facing budget constraints, language services can compete with other high-need priorities such as special education, mental health services, and building improvements.

State officials continue to review how funding formulas and accountability systems address the unique needs of multilingual students. Policymakers are also examining how language proficiency data is used to evaluate school performance, arguing that traditional assessment models often fail to capture the full scope of academic growth among students still acquiring English.

The rapid rise in multilingual enrollment has also intensified broader conversations about how teacher training programs, certification pathways, and professional development must evolve to prepare educators for increasingly diverse classrooms.

Colleges and universities across New Jersey are expanding bilingual education pipelines and alternative certification routes, aiming to attract multilingual professionals into teaching careers. District leaders say sustained investment in those pipelines will be essential if the state hopes to keep pace with demographic change over the next decade.

The classroom realities now unfolding across New Jersey reflect a permanent shift, not a temporary surge. Demographers project that language diversity will continue to expand statewide as new families arrive and established communities grow.

For New Jersey’s public schools, multilingual education is no longer a specialized service operating on the margins. It is becoming a central component of how the state delivers instruction, builds curriculum, and prepares students for a multilingual global economy.

Ongoing statewide coverage of instructional policy, student outcomes, and school innovation—including the expanding role of language education—can be followed through Sunset Daily News’ education reporting, which continues to track how districts adapt to one of the most consequential transformations in New Jersey’s public education system.