お菓子☆まとめ売り!!!531

(税込) 送料込み

商品の説明

⚠️2月賞味期限分までは抜きません⚠️

⚠️お菓子の交換はしません。箱いっぱいにお菓子を入れています。大きさや形が違う他のものを入れれません!

ご理解願います(´;ω;`)

⚠️透明テープでぐるぐる巻きの物があります!落下飛散防止で元からです。気になる方は購入をお控えください。

⚠️予告無く箱からバラして梱包する場合があります。嫌な方は事前にお伝えください。

(梱包箱の大きさにより差額分上乗せになる事もあります)

賞味期限

【527】

ブルボンプチポテトコンソメ10袋 2024.5

ブルボンプチポテトうすしお10袋 2024.6

ブルボンプチラングドシャ20袋 2024.4.21

カルパス50個入 2024.3.22

ブラックサンダー20本 2024.6

スーパーBIGチョコ20入 2024.4.30

どらチョコ20入 2024.2.25

チョコケーキ2枚×10袋 2024.2.24

ぷるんぷるんQooみかん味6個 2024.5.6

ぷるんぷるんQooぶどう味6個 2024.6.17

ぷるんぷるんQooりんご味12個 2024.4.22と2024.6.3

エンゼルパイバニラ8個×2袋 2024.4

オロナミンCローヤルポリス6本 2024.9

カルピス由来の乳酸菌科学100ml6個 2024.6

スープ春雨ワンタン6個 2024.3.14

とうふとわかめの味噌汁6個 2024.3.10

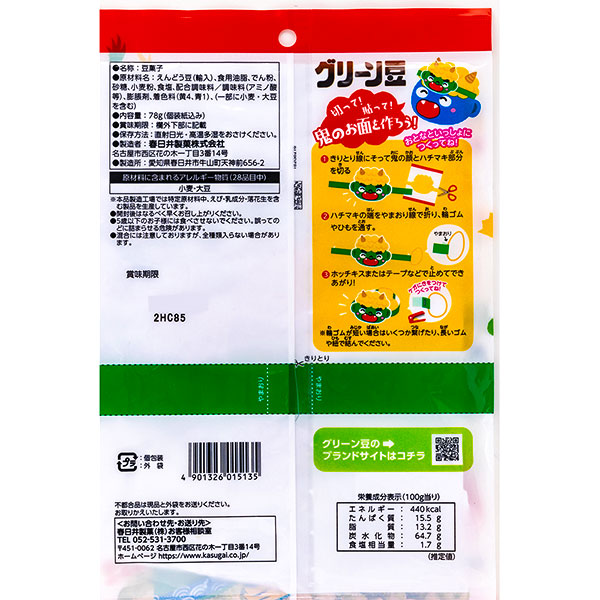

【531】

チップスター8種類8個入 2024.10

シルベーヌザッハトルテ6個✕3箱 2024.4.2

シルベーヌ6個✕3箱 2024.4.18

トッポ15箱 2024.8

小枝5箱 2024.8

チョコクランチポット苺味50個 2024.5.5

カルピス✕MINTIAタブ10個入 2024.6

⚠️お菓子輸送時の割れやチョコレートの溶け等あるかもしれませんので十分理解されたのち購入してください。

コメント無しの即購入大歓迎です(*´ω`*)

お菓子の交換やバラ売りはしません。

お値下げは考えておりません。

#お菓子まとめ売り

#お菓子セット

#お菓子詰合せ商品の情報

| カテゴリー | 食品・飲料・酒 > 食品 > 菓子 |

|---|---|

| 商品の状態 | 新品、未使用 |

本物品質の お菓子☆まとめ売り!!!531 -菓子

超歓迎】 お菓子☆まとめ売り!!!531 -菓子

ラウンド お菓子☆まとめ売り!!!531 - 菓子 | emperornet.academy

保存料・着色料・香料無添加 ほろっとほどける【ほろほろくっきぃ

チョコ菓子ギフトセット♡お菓子15袋☆紅茶付き♡ スイーツ・お菓子

お菓子にはそれぞれ意味がある?【特別な人】にあげるなら✨もらって

お菓子のアレンジレシピはおかずになる?こっそり作って食事に出して

お菓子ボックス作り その3 箱詰め!→YouTubeに動画もアップしています

SNSで話題の商品が大集合『キラキラドンキ 』の韓国お菓子ベスト5は

ミニストップ】「神の食べもの」「めちゃくちゃ好き」SNS大絶賛の《ご

2024年最新】ミンティア カルピスの人気アイテム - メルカリ

テディベア クッキー くま お菓子 【クマちゃんBOX】 焼き菓子

鎌倉チョコサンドだょ 10個入: 鎌倉五郎本店お取り寄せスイーツ|通販

たっくさん焼いた焼き菓子をラッピングしてお菓子ボックスにしましたー

プレゼント 子供 誕生日 可愛い お菓子【動物クッキー・ビスケットのお

ダイソーの4連パックのお菓子が3連になってるううううう!!!「こんな

スイスミスココアミックス &ロッキーマウンテンマシュマロ : set531

お菓子のまとめ売り - 菓子

チョコ菓子ギフトセット♡お菓子15袋☆紅茶付き♡ スイーツ・お菓子

かわいいお菓子の袋でちょいリメイク!100均材料&すき間時間でできる

先日購入した業務スーパーのお菓子レビュー | jiminchoo_akoが投稿した

楽天市場】節分グリーン豆{お菓子 まとめ買い}{ギフト 誕生日}{子ども

トラントセット-trente sept- 加古川自宅お菓子工房 (@37tresepmarie

ミニツク to 高山 都さん】盛るだけでお店のようなたたずまいに

かわいい お菓子 うさぎ クッキー 【ウサちゃんBOX】 焼き菓子

昔懐かしい 小魚アーモンド 6g×18袋 送料無料 小魚 アーモンド お菓子

2023秋冬NEW>パフェ缶 ケーキ缶 大容量330ml 3種バラエティセット

みんなで協力して作り上げる!体にやさしいお菓子の「セサミ香房

よっちゃん酢漬けいか 85g よっちゃん食品工業 懐かしの 酢漬けいか

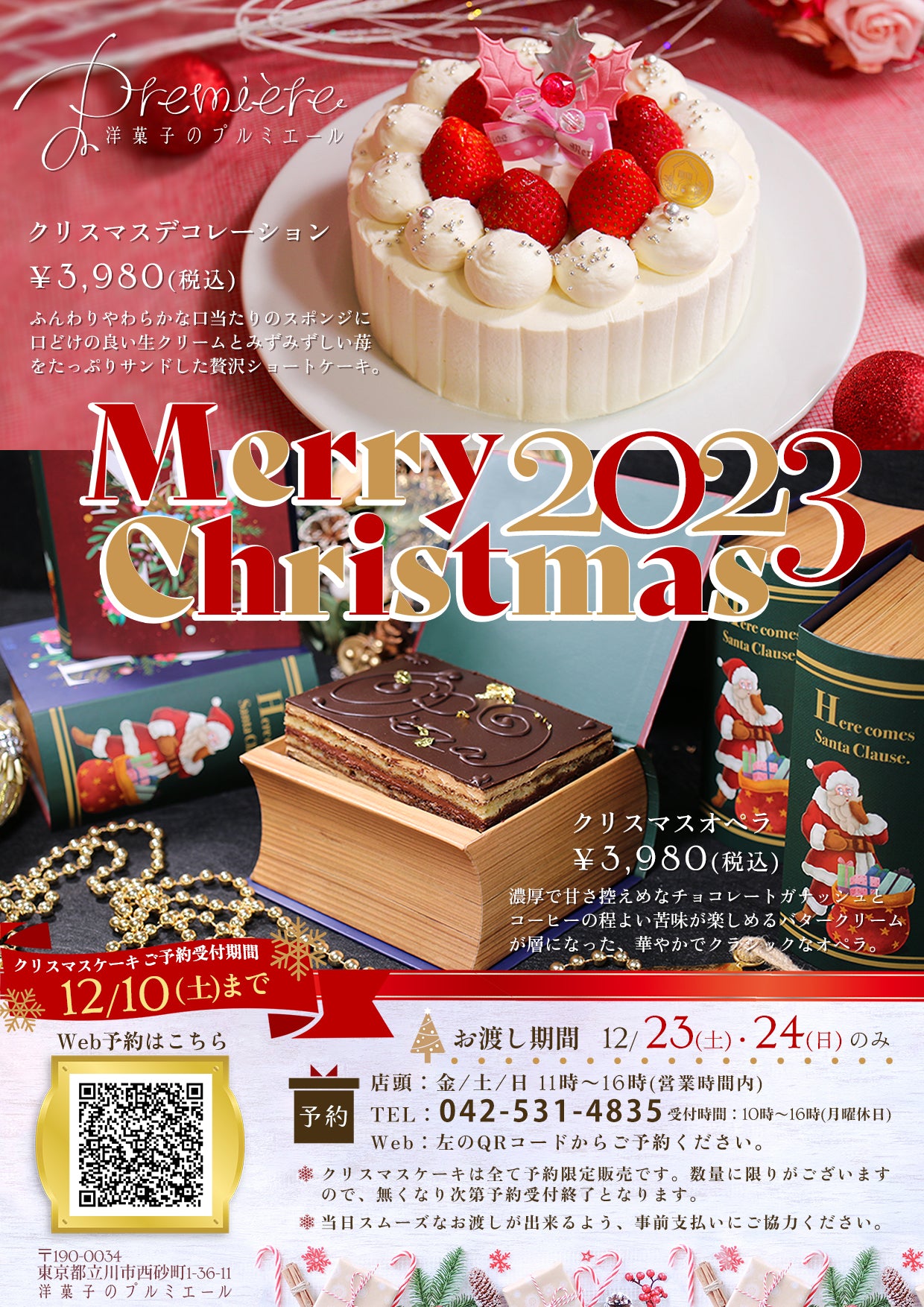

洋菓子プルミエール」の人気商品4選を紹介!おしゃれな見た目で大人

モンブランフジヤ オンラインショップ

チョコやお菓子の包み紙、捨てるの待ったーー!便利アイテムに大変身

お菓子 まとめ売り - 菓子

可愛い お菓子 誕生日 プレゼント 【パンダビスケットのクッキー缶

公式 九州産 さつまいもグラッセ お茶菓子 お菓子 チャック付き

プルミエールのクリスマスケーキ – 洋菓子のプルミエール

お菓子の空き箱、すぐポイはもったいない!徹底的に使い尽くす4つの

お菓子にはそれぞれ意味がある?【特別な人】にあげるなら✨もらって

お菓子☆まとめ売り!!!531 限定価格セール! 菓子 kiti.com.kw

シュガーバターの木 コレクション 46袋入: シュガーバターの木お

商品の情報

メルカリ安心への取り組み

お金は事務局に支払われ、評価後に振り込まれます

出品者

スピード発送

この出品者は平均24時間以内に発送しています